*********************************************

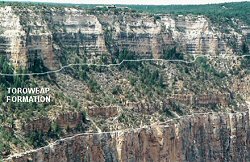

Toroweap Formation

Permian Period, 275 Million Years Old, 250 Feet Thick

Vegetated slope with low cliff near base

Sandwiched between the Kaibab and Coconino cliffs lies an inconspicuous sloping formation covered with trees. There is a moderate sized limestone cliff 4/5 of the way down the slope. This slope-cliff-slope is the Toroweap Formation. Hikers first notice the formation when they descend to the first pinkish mudstone layer. From the rim, look for these pink beds just below the Kaibab cliff. The Toroweap has one of the most diverse rock varieties in the Canyon: sandstone, mudstone redbeds, gypsum, limestone and dolomite.

The Toroweap was deposited near the shore of a shallow sea whose incursion was interrupted by

several temporary retreats. The retreats left the sediments exposed to air in salty tidal mudflats.

The Toroweap environment may have been analogous to this scene from the Gulf of California. North and west of

the Canyon, the Toroweap contains gypsum and salt deposits attesting to evaporation in a shallow sea.

The Toroweap is not as fossil-rich as the Kaibab Formation. The limestone cliff part way down, called the Brady Canyon Member, represents the deepest water and contains various shellfish fossils. A more open marine fauna to the west characterized by brachiopods and crinoids shows that the sea was deeper there. Here and to the east the fossils are mostly near-shore forms, especially snails, scaphopods and clams.

The following story pretends that people were alive when this formation was laid down. But it was long before people. The purpose is to immerse ourselves in the time period--to imagine being there.

Our Tribe in Toroweap Time

For thousands of years our people have been the salt-gatherers of Pangaea. Our trade routes have broken eastward through the icy passes of Vermontia, the vast mountains that separate us from Europe. There is no Atlantic Ocean. Vermontia will one day erode down to its roots, and joggers will pass by in Central Park, New York. But we don't know that yet, and for now we have a land route to Europe and Asia.